In our previous posts (Tutorial 1 – Note Names, Placement and Major Scale and Tutorial 2 – Minor Scale Construction and Introduction to “Circle Of Fifths”) we were talking about a method of constructing Major and Minor scales, as well as we’ve introduced a very handy music tool – “Circle of Fifths”. Today, we are going to introduce another very important music concept – “Scale Spelling”. With a help of that we will discover the whole new world of music scales which is far wider than Minor and Major.

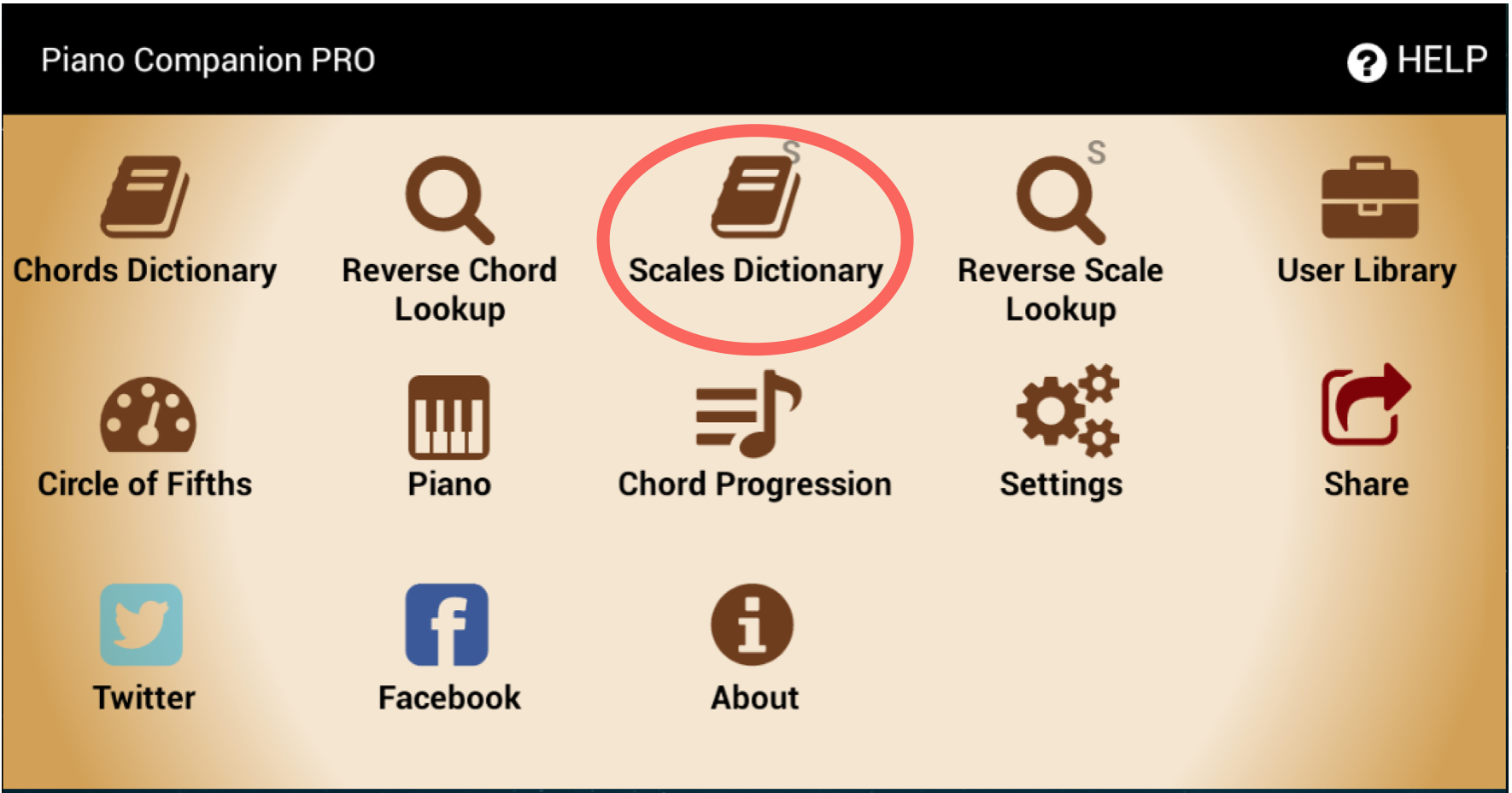

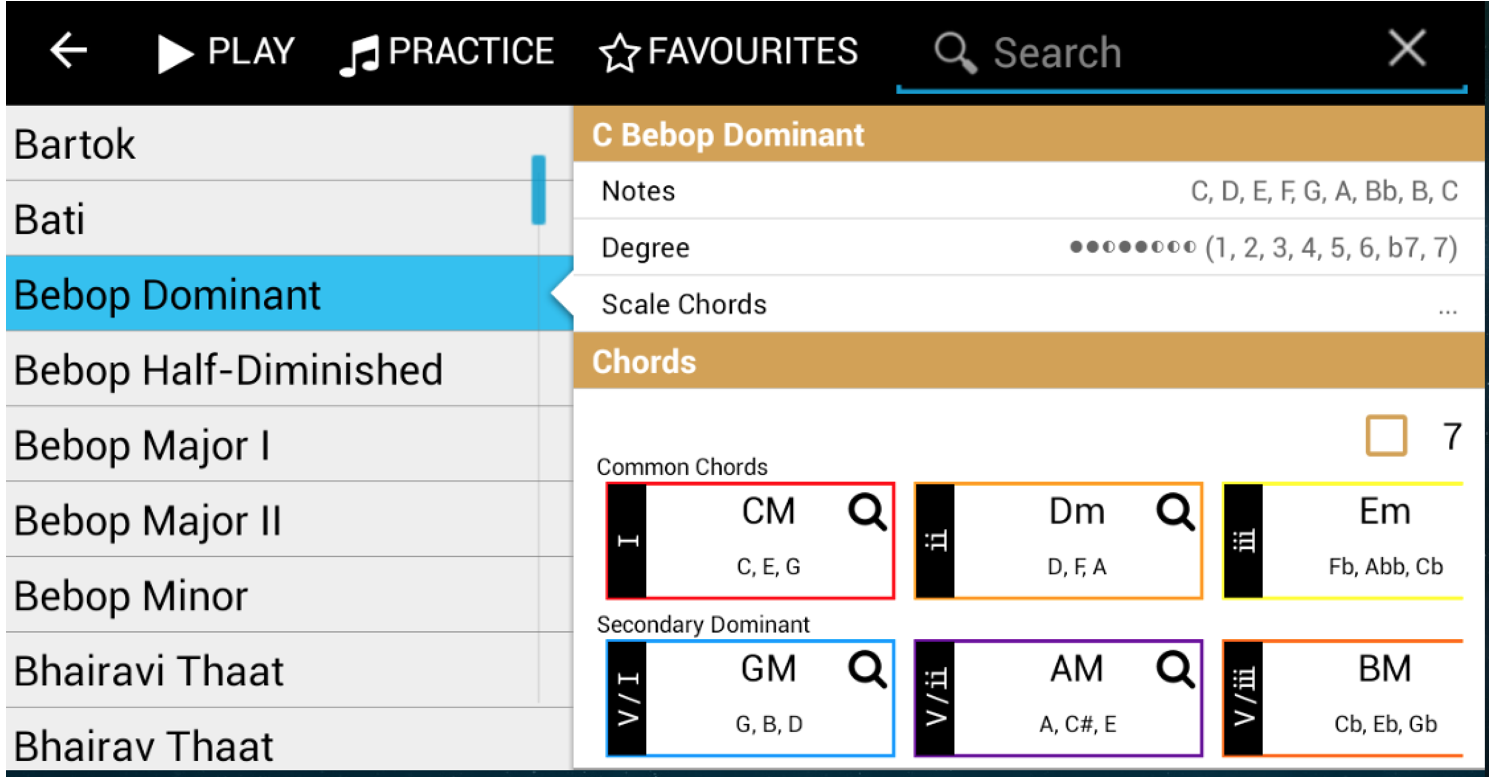

As everyone already knows, all notes in a scale have letters. We also know that there are 8 notes in a scale, with 7 distinct ones. Now, all notes/letters from the scale also have a corresponding number. These numbers are referred to as “scale spelling”. Please open a “Piano Companion” application and choose “Scales Dictionary”.

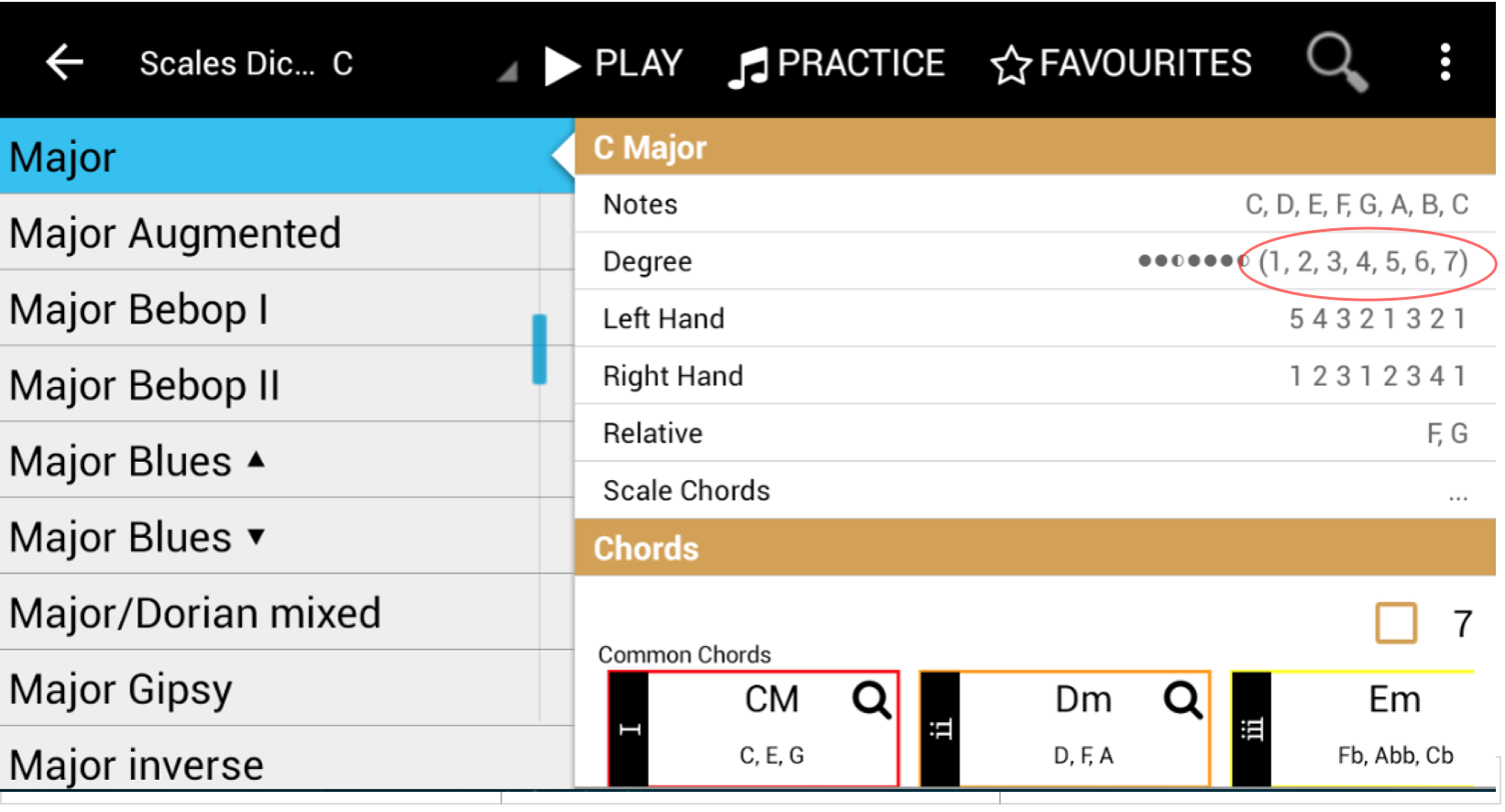

By the application default settings, the first scale that you see is a Major scale. Just have a look at the numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) – this exactly what we call a “Scale Spelling”.

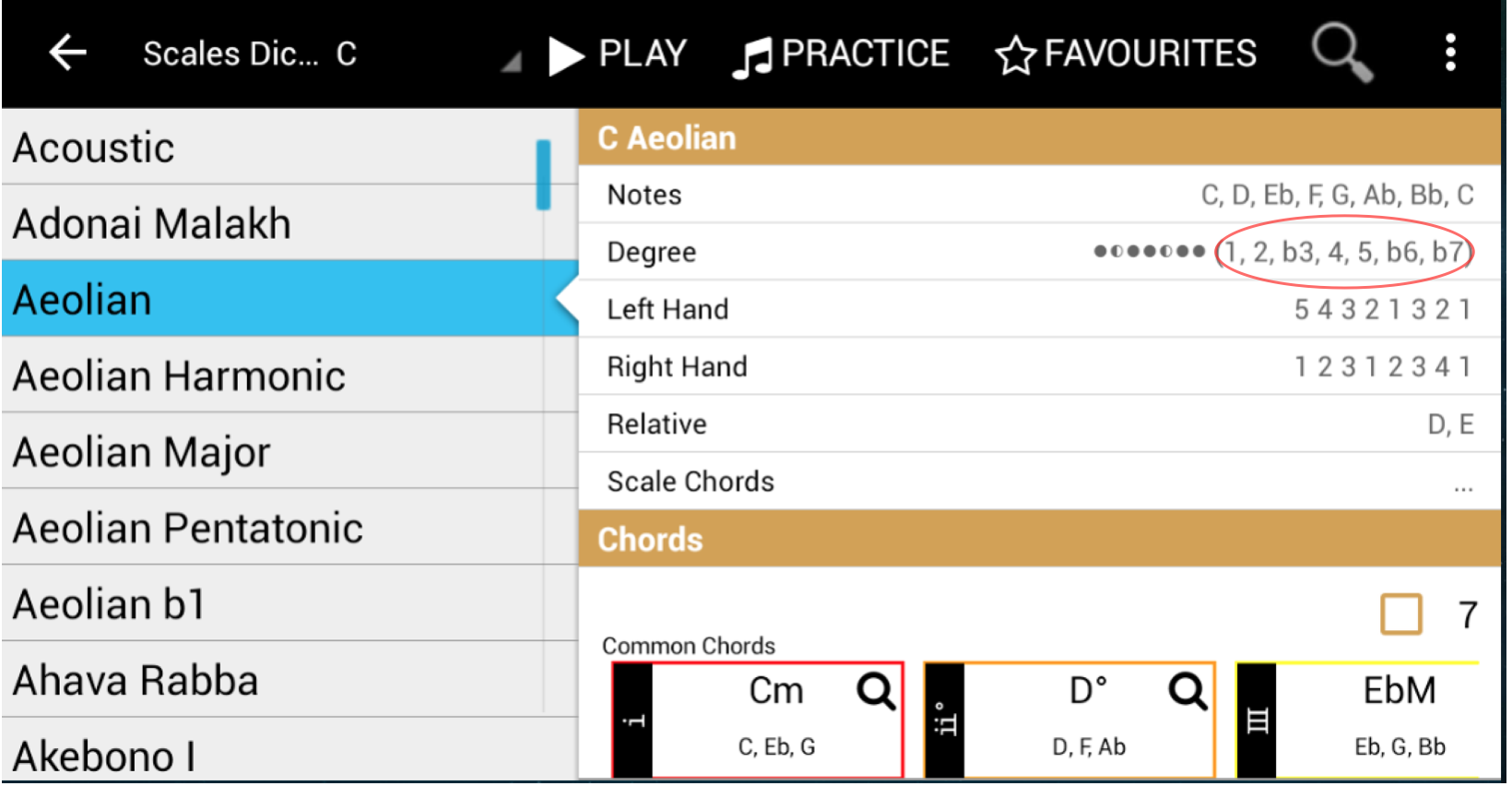

Let’s choose “Aeolian” (Minor) scale from the list.

Can you see that the “Scale Spelling” for Aeolian scale is different from the Ionian one (Major)? As you may guess, if you chose any other scale from “Scales Dictionary” it will be different too. But let’s take a closer look at Ionian and Aeolian scale spellings.

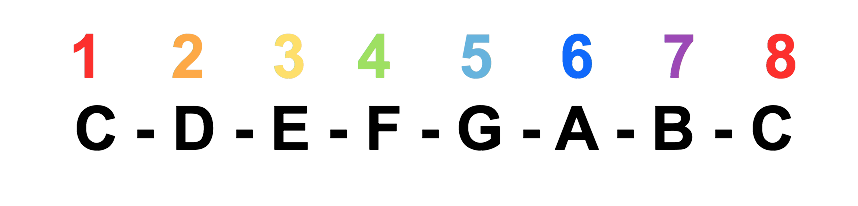

It will be very helpful, if you take a piece of paper and write down a C Major scale and put 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 (1) above every note of the scale. If you do it correctly, that’s how it should look like:

Each note of the scale has it is own number, which we always write above the note names. Let’s write a C Minor and the “Scale Spelling” for Aeolian scale above it.

Even if you never learnt music before, we’ve already mentioned that “b” – flats are responsible for bringing notes DOWN for one semitone, whereas “#” – sharps are responsible for bringing notes UP for one semitone. As you can see the spelling for Aeolian scale (Minor) has b3, b6 and b7 in it. The notes that are below these numbers, also have flats: Eb, Ab and Bb. Isn’t that simple? The scale spelling is like a clue for any musician. Let’s say, you know only a construction method for a Major scale using specific pattern (2-2-1-2-2-2-1) and have no idea how to create any other one, but there is a scale spelling for Minor scale in front of your eyes. By writing your Major scale and putting this scale spelling above the notes (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7, 8) you’ll be easily able to add necessary flats to notes and finally get your Minor scale. The same method applies to any other existing scale in the music world. However, you should follow 2 simple rules:

1) The letters (notes) MUST always correspond to the assigned number (spelling).

2) There may not be notes that share the same name in the scale

What does it mean? Literally, you just need to choose correct enharmonic names for your notes. For example in C Minor (Aeolian) you can’t put “D#” under the number “b3” because “D” is already referred to your second note, the number “2” of the spelling. The same applies to “Ab” and “Bb”. You can’t put “G#“ and “A#” instead. We are quite sure that this fact is very obvious, but still sometimes people can forget, so keeping this tip in mind will help not to make mistakes.

Ok, the time has come, to find out why a Major scale is called “Ionian”, and why a Minor scale is called “Aeolian”. The reason why these scales have more specific names, simply because there are different types of Major and Minor scales. Most of the scales can be divided into Major and Minor families. So let’s have a look at 7 scales that are mostly used in today’s music:

SCALE SPELLINGS: IOANIAN - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 DORIAN - 1 2 b3 4 5 6 b7 PHRYGIAN - 1 b2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 LYDIAN - 1 2 3 #4 5 6 7 MIXOLYDIAN - 1 2 3 4 5 6 b7 AEOLIAN - 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 LOCRIAN - 1 b2 b3 4 b5 b6 b7

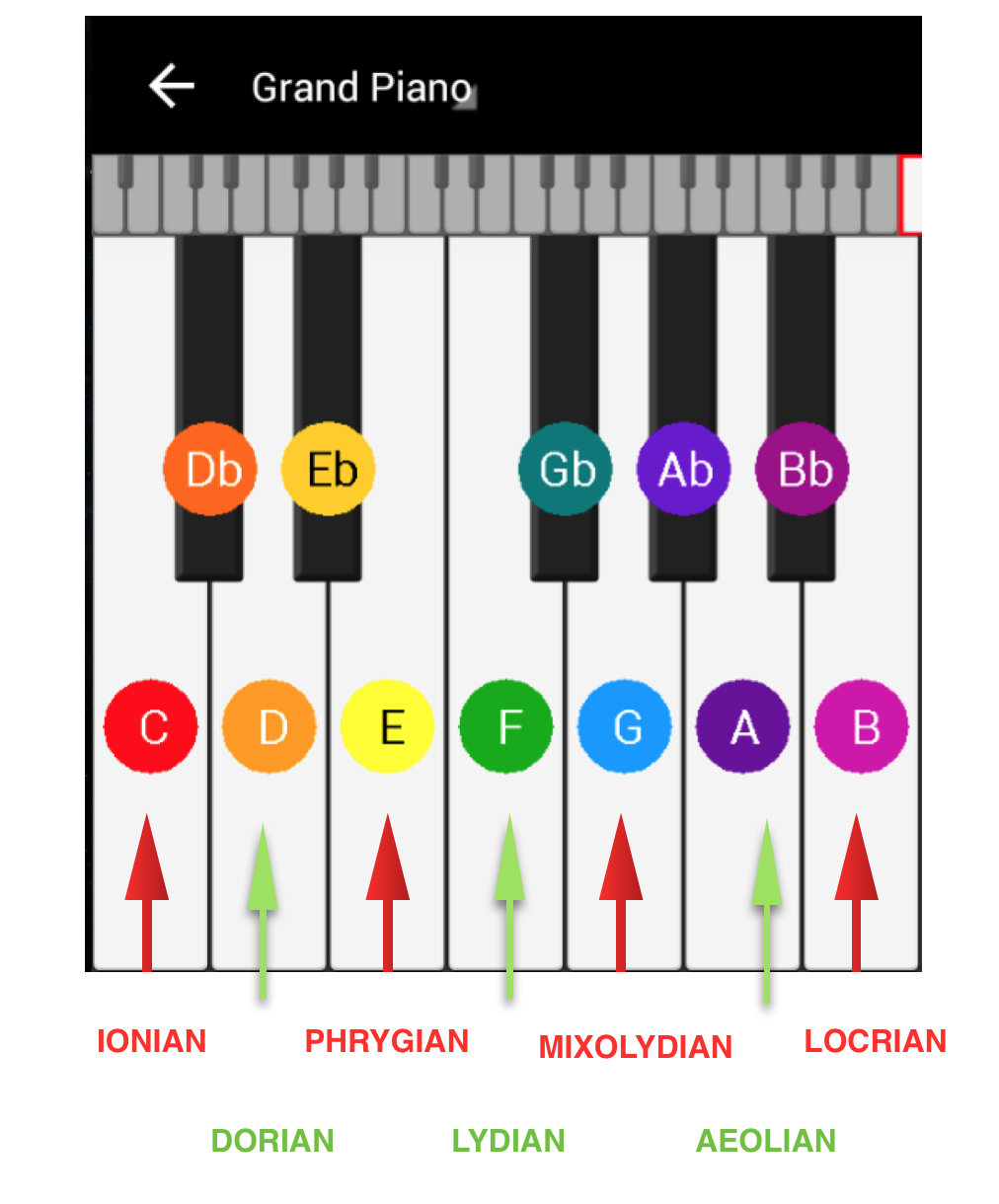

The picture above points us to the different types of Major and Minor scales that have all white notes in it like C Ionian and A Aeolian. There is exactly the same thing for D Dorian, E Phrygian, F Lydian and etc. As we’ve mentioned earlier all scales can be divided into 2 families: Major and Minor. In this case we have:

Major scales:

- Ionian

- Lydian

- Mixolydian

Minor scales:

- Dorian

- Phrygian

- Aeolian

- Locrian

The most used scales in Popular music are Ionian, Aeolian, Mixolydian and Dorian. Less used is Lydian, because of the #4 which gives quite dissonant sound, that may feel unpleasant the ears. The most famous example of Lydian scale use, you can hear in known by everybody “Simpsons” music theme. Phrygian and Locrian are common in soundtracks and background music for Horror movies. Just have a listen, and you will understand why! These scales often used in Metal music as well.

The most accurate definition of the scale family would by checking thr 3rd note of the mode. If the 3rd number of the scale spelling is flattened, then it belongs to the Minor scale family. By the way, have you noticed that there are more Minor scales than Major ones? There is exactly the same thing for chords. There are more Minor chords that you can construct from the scale, than Major ones.

If you have a proper look to the scale spellings of these modes (scales), you’ll see how easy it is to construct any mode you like, if simply have a scale spelling in front of your eyes. All you have to do is just to construct Ionian scale and flatten or sharpen necessary notes, according to the spelling. Isn’t that simple? It’s definitely is!

We believe that we’ve shared enough information for today and there is a lot to think about and experiment with. And don’t forget to check out your “Scale Dictionary” in “Piano Companion” which has so many more scales to play with!

Just keep an eye on our blog and you will find so much more interesting about music.